BELLIGERENT PIANO is like an old car to which I'm deeply attached but can't seem to get running correctly, or in the right direction. It started as a simple exercise in character development, but has grown into something much more complex than my original aim. The first installment is featured in Happy Hour in America #1.

Episode #1 introduces the main character, Jackie No-name. It also introduces an event that serves to push the story into its intitial stages - a burglary and a murder that take place at a warehouse owned by a certain W.D. Quelt. Belligerent Piano is, in part, an homage to all of the crime comics, hardboiled fiction, and film noir movies that have captured my attention since I was a kid. What I wanted to do with BP was combine the sensibility of 1940's era crime comics, and more specifically something of what I remembered of Will Eisner's The Spirit, with a surreality influenced by my own ideas of American mythology. When I first started working on the story, when I was in my early twenties, I was very much feeling the post-college hang-over of taking my artistic and literary aspirations and interests too seriously, and wanted to return to comics - something I hadn't really thought much about since I was fourteen or fifteen. The first big influence on me was the Spirit. While I was growing up, Kitchen Sink Press had been reprinting Eisner's work from the 1940's, and while most of my friends read Daredevil or the X-Men, I really couldn't get enough of Eisner's classic hero. Incidentally, none of those friends understood my fascination with the old crime fighter. I guess the era from which the Spirit originated was too far removed for them, but I've always had an inexplicable affinity to eras that are several generations removed from my own. At the same time, old issues of EC's Crime and Shock Suspenstories were being rereleased, as well. That stuff was also very influencial - specifically the work of Johnny Craig and Al Feldstein - both of whom, along with Jack Cole, played a role in the development of my graphic, "comic book" style.

I mention all of this because, with Belligerent Piano, I wanted to get back to something that would be creatively "fun", and where imagination could run wild. The landscape of Belligerent Piano isn't quite America in the late 1940's, but instead my mythical idea of America in the late 1940's - it's meant to be more dreamlike than real - a sort of artistic understanding with myself that, since I could never travel to the that era, it could only be visited through imagination. And I suspect that the way I created it has less to do with what it was actually like, and more to do with how I wish it could've been. My intension was - and is - to create a mythological, cinematic 1940's rather than a realistic one. In other words, the 1940's of my dreams.

...so, the story begins with a murder and a burglary - both cliches among the cliches of 1940's crime comics and B-grade pulp fiction. And I wanted to embrace all of that: Dopey cops, sinister bad guys, bizarre and mishapen small time crooks, losers, and thugs; bombshell sirens, all of it. Even a semi-amnesiatic, morally ambiguous protagonist; an ex-soldier, an aimless drifter who doesn't know his own name - the result of an undisclosed injury he endured during World War II.

Episode #1 finds our protagonist, Jackie, hopping a freight train out of an unknown city, ostensibly to escape pursuit from a silhouetted character standing under a bridge. A telling dream occurs after he falls asleep, in which the introduction to him is broadened and some foreshadowing occurs.

The next morning, he's shaken from this dream by an insane, one-eyed vagrant who throws him off the train. Eventually he hitchhikes into the town of Circus City, where the Quelt Co. warehouse had been burglarized the night before.

Each of the main characters in BP were initially meant to serve some kind of mythological significance, the more unique to American culture the better. BP was the stage onto which I first conceived of playing out my personal take on the Great American Mythological Drama. Jackie represents the drifter, the aimless wanderer. Making him an amnesiac was meant to speak metaphorically to the cultural importance that Americans are, in general, arguably less interested in their pasts - geneologies, cultural heritages, etc. - than are other cultures. Or, as in many cases, "aware" of their own histories. America, after all, has always represented the place one could come in order to recreate themselves, start over, forge a new identity, forget the past; the country where one wouldn't be limited because of the societal position into which they were born. In this way, Jackie represents that side of the American mind. Kind of.

And it's at this point where the story began to go vertical rather than horizontal - upward instead of forward. Jackie became something much more meaningful to me than the story itself. Over time, I started to think of him as a myth, and that myth broadened in all directions. The supplementary pamplet MYTH OF JACK, and its corresponding CD of spoken word sketches and "folk songs" - much of which stems from the text of the first installment of the story - is dedicated to, and proof of, that broadening myth.

(cover: Myth of Jack)

(inside illustration: Myth of Jack. At the time I began working on this project, an exhibit of the illuminated works of William Blake was on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I went several times and, although I was already familiar with Blake's work, had never been so moved by it.)

(inside page illustration: Myth of Jack)

(2 page spread from Myth of Jack)

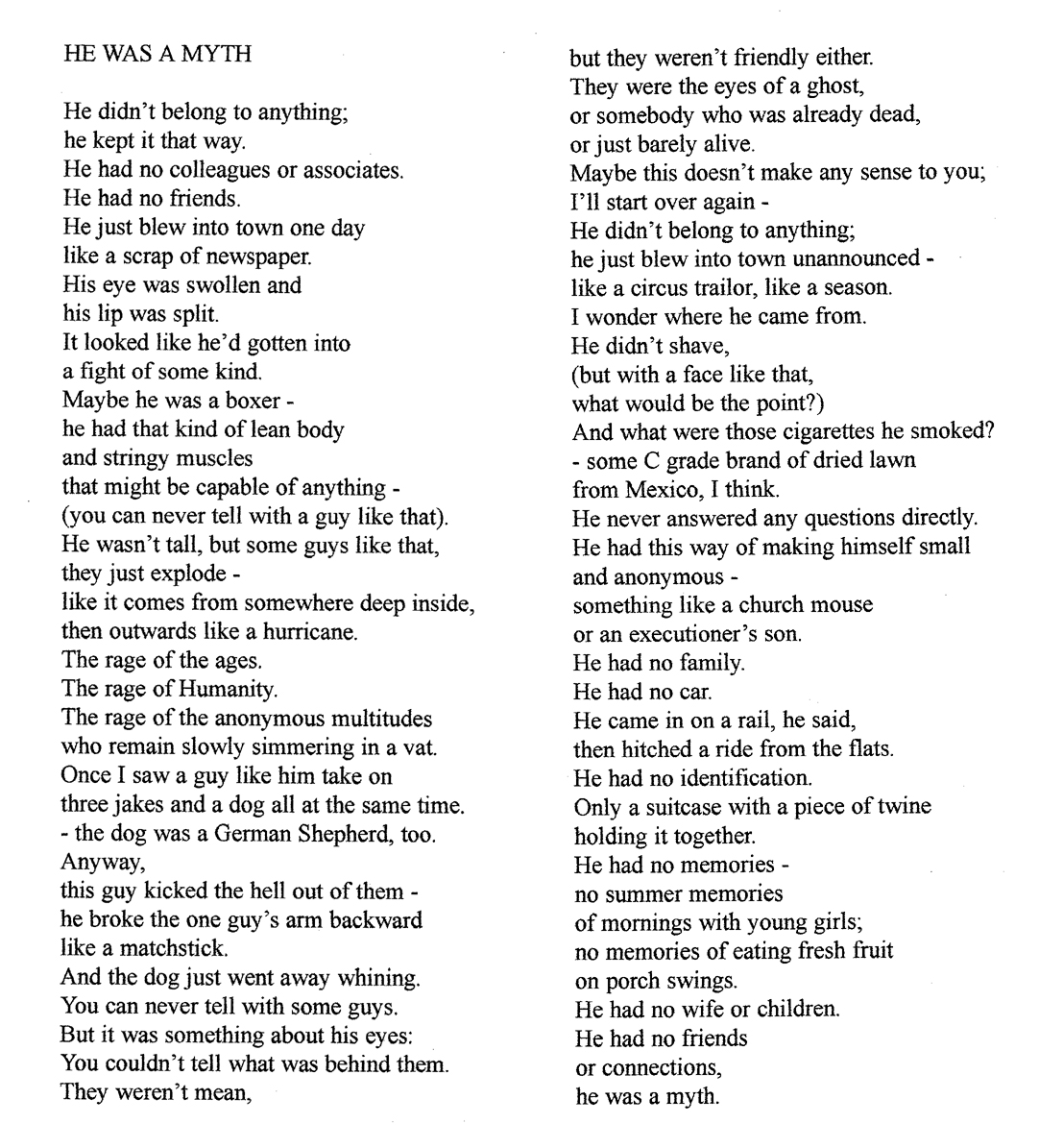

(Text from Myth of Jack: "HE WAS A MYTH" - all text original except for the final lines, "he had no friends or connections; he was a myth", from Thomas Wolfe's "Look Homeward, Angel", a passage that, to me, sums up Jackie's persona perfectly.)

Physically and (to a somewhat lesser degree) tempermentally, Jackie has always appeared to me as something between Harrison Ford in Ridley Scott's Blade Runner and Jean-Paul Belmondo in Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless (hence the everpresent cigarette). The anonymous quality to Jackie No-name stems from two things: John Doe - Jack being another name for John - and Clint Eastwood's iconic portrayal of the Man with No Name in Sergio Leone's trilogy honoring American westerns. The heavy shadows under Jackie's eyes - his "mask", so to speak - which is meant to be his signature facial characteristic (along with the cigarette) is my humble tribute to Eisner's Spirit.

The above-mentioned influences were all dreamed up over fifteen years ago. How much of it still pertains is hard to say. Hopefully Jackie becomes his own man, rises above his influences. I'm not sure, don't know if it matters

I mention all of the background influences to Jackie reluctantly out of concern that it might shape the first-time viewer's image of him too much. I hope you see him however you want to see him. On the other hand, I thought it might be interesting for you to imagine how I see him as well.

Happy Hour in America #1 ($3.95), the Myth of Jack pamphlet ($2.00) and the Myth of Jack CD (2.00) are available upon request.