SMOKE MY FUTURE

A surreal red light shone on the painted head of a doll. The doll’s head sat on a windowsill, its features were facing outward, as if on display. There was violin music playing from inside the room, sounding muffled and maudlin. Beneath the window, the woman lumbered stiffly up the staircase, nursing one leg and leaning heavily on the rail, which creaked under her wieght.

SMOKE MY FUTURE

A surreal red light shone on the painted head of a doll. The doll’s head sat on a windowsill, its features were facing outward, as if on display. There was violin music playing from inside the room, sounding muffled and maudlin. Beneath the window, the woman lumbered stiffly up the staircase, nursing one leg and leaning heavily on the rail, which creaked under her wieght.

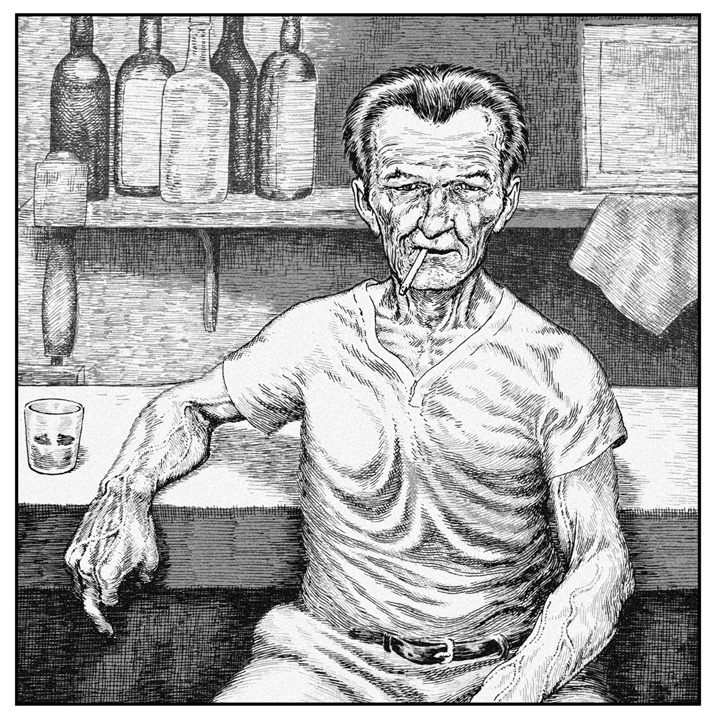

"Your future’s in my pipe," she said, "I’m smoking your future," and she smiled while drawing deeply on her pipe.

"That’s how it is," she continued, "I smoke everybody’s future. Everybody that walks by. If I see them or not. It don’t matter."

She stopped to inspect me for a moment. Her expression became roguish. I half expected her to wink. I tried to watch the trail of my future plume from her pipe, but it was a breezy night and the wind blew away any evidence of my future’s remains.

"See," she said, "You have no more future. I smoked it."